Women in Classics in the UK: Numbers and Issues

Analysis of Findings – The WCC Survey

Women in Classics in the UK: Numbers and Issues

By Victoria Leonard and Irene Salvo

With contributions from Emma Bridges, Kate Cook, Lisa Eberle, Katherine McDonald and Amy Russell

This piece has been published simultaneously in the CUCD Bulletin, where you can download this report as a PDF document.

INTRODUCTION

Following the creation of the Women’s Classical Committee, one of our first tasks was to establish the state of the field for women in Classics in the UK: what kind of challenges and obstacles do women face? What kind of professional roles do women occupy, and where are they excluded? What kind of support do women benefit from, and what is lacking? We decided to construct a survey in order to ask people directly about their experiences as well as collecting some useful quantitative data.

Here we present our analysis of the collective response to the survey. Invitation to fill in the survey was made through the Classicists Liverpool List, Twitter, and Facebook, and 417 responses were given. An evident bias inherent within the data is that those who are adversely affected by the issues raised and who have a corresponding higher level of awareness are more likely to complete the survey, potentially skewing the results to reflect a more gloomy situation than is the case. Furthermore, the random nature of participants prevents the survey from being statistically representative.[1] Despite the limitations of the data collected, the results of the survey reveal in a clear and consistent manner the depressing, unsatisfactory, and unequal situation faced by female classicists. Moreover, some of the issues raised by the survey such as sexual harassment are so serious that they need urgent attention, regardless of how representative (or not) the data is.

[1] To calculate the population size and the corresponding optimal sample size the forthcoming data from the Council of University Classical Departments (CUCD) statistics for the year 2015/16 on the student and staff population could be used, to which we could add the statistics for Classics teachers and researchers in non-HEIs (Higher Education Institutions).

1. Composing the Survey (Victoria Leonard)

The construction of the survey proved to be a much larger task than we first thought and posed a real intellectual challenge, raising some fundamental problems about the scope of our target audience, and the information we wanted to gather. The survey was hosted by Google Forms and was put together using feedback generated from the Committee on Slack.com. Both online platforms were invaluable tools: they enabled the survey to be constructed democratically, allowing swift response to criticism and the instant and public integration of changes. We wanted the survey to focus on the experiences of primarily but not exclusively female classicists at moments or situations of particular professional vulnerability – for instance, balancing considerable parenting or caring responsibilities, being Early Career and female, or experiencing mental or physical health issues.

The survey was divided into six sections:

- Personal Information

- Gender in Professional Environments

- Gender in Professional Interactions

- Gendered Work: Parenting and Caring

- Mental Health and Disability Issues

- Women in Classics: The State of the Field

The first section, ‘Personal Information’, asked the current occupational status of respondents, their age, their gender, and their field of study. Section two, ‘Gender in Professional Environments’, covered working and contractual hours, the gender ratio between students, staff and senior staff, and casualization. Section three, ‘Gender in Professional Interactions’, asked respondents about gender or sex-based discrimination, if gender or sex-based issues affected career progression, and if respondents had experienced inappropriate or unwelcome sexual behaviour. Section four, ‘Gendered Work: Parenting and Caring’, asked respondents about the intersection between professional academic life and parenting and caring responsibilities and choices. It also asked about the provisions and facilities employers made for those parenting and caring whilst working. Section five, ‘Mental Health and Disability Issues’, asked about mental health and disability issues. Section six, ‘The State of the Field’, returned to a broader perspective, asking respondents about the support they received, career progression for women in Classics, and what aims and initiatives respondents wanted to see the WCC introduce.

Three issues were central in the construction of the survey: one, who are we going to ask? Two, what are we going to ask them? And three, how are we going to ask?

1.1 Respondents (Who are we going to ask?)

Many of the issues the survey raised quite clearly affected all genders, and not exclusively women. We wanted to be inclusive and encourage people of all genders to complete the survey. This impulse was partly an acknowledgement of reverse discrimination, that gender and sex-based discrimination does not just harm women, and that the experiences of men, to use those polarising and problematic categories briefly, were felt to be of equal value. Similarly, in terms of professional demographic we decided to keep the survey as open as possible. We invited anyone studying, trained in, or working in the field of Classics to complete the survey. ‘Classics’ itself was very broadly defined, reaching back to prehistory and up to the Middle Ages. We anticipated that classicists working in non-Higher Education Institutions, particularly school teachers, would make contributions, as well as an audience spanning undergraduates to full-time academic staff in Higher Education Institutions. The inflexible aspect of the survey was geographical in that we required information contributed to be based on experience from the UK.

1.2 Language and Categorisation (What are we going to ask?)

Our second challenge was how to formulate and phrase the questions. During the early stages of drafting it was difficult to avoid confirmation bias, where an expected answer was imposed on the question; for example, rather than asking how have the effects of casualization damaged your career progress, we asked ‘have you experienced the effects of casualization in your employment?’ with a yes/no choice and a large text-box for detailed answers. We also tried to construct positive questions – rather than asking women in Classics what support is lacking, we asked what kind of support women found beneficial.

We were mindful of the balance between obtaining as much information as possible from our respondents, and not making the form overly long. In early drafts, the format of every answer was a large textbox. However, as much as we would like, realistically respondents were not going to write 500 carefully considered words for every question. Providing convenient tick-boxes or multiple choices would make the form quicker to fill in and make respondents much more likely to complete the form. But categorisation brings its own perils, and it was difficult to decide when to limit categories. For example, Ancient Literature and Ancient Philosophy were included in the ‘Personal Information’ section identifying which field of study participants belonged to, but Classical Reception studies, and other modern theoretical concepts applied to antiquity like feminist theory or postcolonialism, were not represented. The survey ultimately included only two questions with no suggestions or options: ‘Which gender category do you most identify with?’ and ‘What aims or initiatives would you like to see advanced by the WCC in the support of women in classical studies?’ The question about gender was changed just before the form went live after feedback from an undergraduate student suggested that even open categorises including ‘fluid gender identity’ were too restrictive, and that it would be preferable for respondents to describe their own gender rather than providing specific options.

1.3 Relevant Issues and Intersectionality (How are we going to ask?)

The third challenge was deciding on the information we wanted to gain from respondents. The survey was designed to target the experiences of primarily female classicists at particularly vulnerable points or situations; the committee were particularly aware of intersectionality, where issues of gender discrimination and bias converged with additional factors such as sexuality, disability, and ethnicity. Originally, the category of ethnicity was included in the question: ‘Have issues of gender, sex, or sexual orientation affected your career progression?’ But as composition of the form progressed it became clear that mixing these important and complex issues with other factors that may hinder women professionally was unsatisfactory – it felt gestural and inadequate. We decided ultimately that issues of ethnicity were too substantial to be tacked on to the survey and could potentially detract from the WCC’s main focus, gender. Issues of ethnicity and sexuality, it was decided, will be considered intrinsically for future surveys.

THE SURVEY AND DATA PRODUCED

2. Personal Information (Kate Cook)

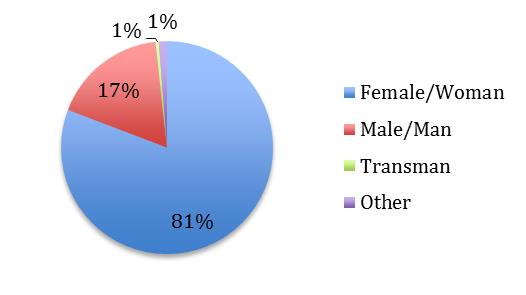

Which gender category do you most identify with?

As might perhaps be expected, the vast majority of respondents self-identified as ‘female/woman’, with 324 answers (81%). However, the survey attracted the interest also of a significant number of male respondents with 70 answers, constituting 17% of responses. Approximately thirteen respondents chose not to answer this question on gender identity, while two respondents were transmen. While the option to self-identify beyond a tick-box approach was valuable, the terms of the question were slightly unclear, or people – as often happens online – were being less than sincere when responding that their gender was ‘heterosexual’ (2), ‘earth gender’ (1), ‘drama’ (1), and ‘theyism’ (1).

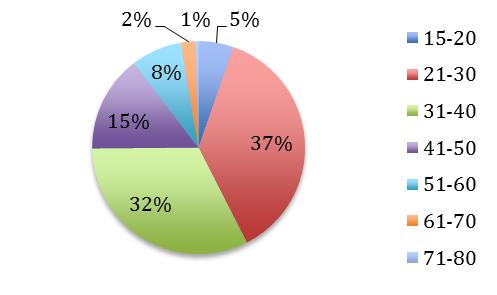

Which age bracket do you belong to?

Respondents were reasonably well-spread across all ages, with the bracket 21-40 the best represented. There were no significant differences between the percentages of male and female respondents falling into each age bracket.

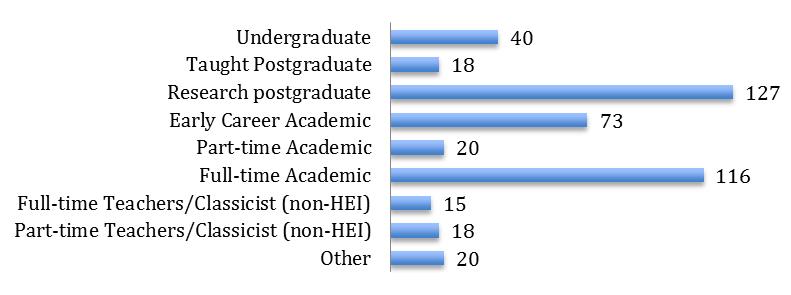

How would you describe your current occupational status?

Substantially more research postgraduates and full-time academics responded than any other group. This might reflect that certain groups are particularly engaged in the issues represented by the WCC, and are therefore more likely to complete the survey. It may also be that the professional demographic of those who completed the survey was determined by the channels through which the survey was advertised, namely the Classicists Liverpool List and social media. There was a reasonable take-up among non-HEI professionals, which itself demonstrates the pertinence of the issues identified in the survey (i.e. access to ancient language teaching, how Classics is taught), and that they begin earlier than Higher Education.

The full-time academic staff category comprised nearly 10% more male than female respondents. However, the spread of female respondents covered a wider range of career categories in general, since there were far more female respondents. Therefore, one should be wary of treating this discrepancy in the full-time academic group as meaningful without a fuller data set.

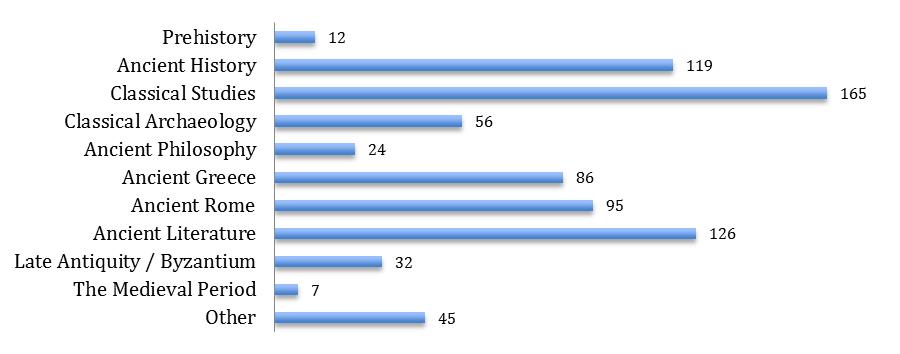

What broadly is your field of study?

Respondents were fairly widely spread across all fields of Classics. Statistically this is hard to quantify as there is likely to be significant overlap between categories, and some may encompass a greater number of subfields than others. There was also a considerable number (45) of ‘Other’ responses, which might include large disciplines such as Epigraphy, Papyrology, and Classical Reception. There were no significant differences between male or female percentages of respondents in particular fields.

3. Gender in professional environments (Amy Russell, with Lisa Eberle on HESA and CUCD data)

The first question in the section asked, ‘How many hours a week on average do you work in your position?’ 16% of respondents were not in employment, while 36% reported that they work fewer than 40 hours per week, and 47% worked more than 40 hours per week. These numbers may be slightly skewed because some respondents chose to give the hours they are contracted to work, while others gave the hours they actually work. The ambiguity only goes to further underline our headline statistic for this section: 52% of respondents reported that they are expected to work more than their contracted hours in order to fulfill the regular duties of their job. 20% did not answer the question about whether they worked more than their contracted hours, but in free-text comments many of those noted that they did not know what their contracted hours were. Several noted that their official job description only covered teaching, but they felt required to contribute extra time to keeping current in their research, either as an implicit requirement of their job or as a necessity for career progression.

3.1 Gender ratio

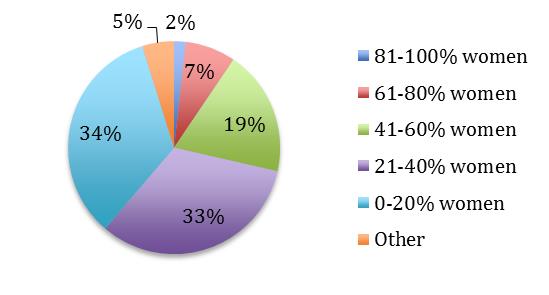

Respondents perceived that the student body is balanced or predominantly female, whilst perceived ratios among staff (and especially senior staff) do not reflect this. Only 19% reported that the balance among senior staff was equal; 66% reported that senior staff were predominantly men, with 34% reporting that as few as one in five senior members of staff were women. At each level of seniority, the perceived representation of women decreases (the infamous ‘leaky pipeline’).

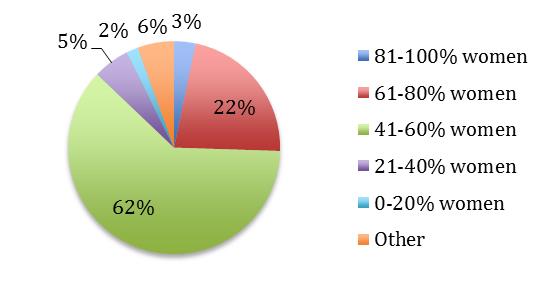

In your professional environment what broadly is the gender ratio between students?

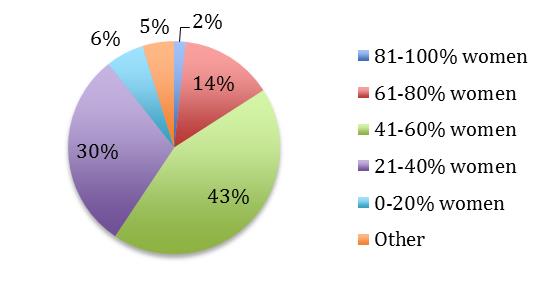

In your professional environment what broadly is the gender ratio between staff?

In your professional environment what broadly is the gender ratio between senior staff?

According to the information provided by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) for 2014/15, while about the same number of women as men are now being employed in Classics, more women than men work part-time, and more women than men have temporary contracts. Of 105 Classics Professors in the UK, only 25 are women, equivalent to a meager 23.8%. Conversely, in what HESA terms ‘Other contract levels’ women outnumber men by a 3% margin. The impression that emerges from our respondents on career progression and security seems to reflect accurately the situation in the UK. A look at age distribution enables some traction on longer-term developments. In brief, the younger people in the field are, the more likely they are to be female. Classicists under 35 right now are more likely to be female than male (56%). Therefore, if we momentarily disregard the effects of the ‘leaky pipeline’, one could expect that in fifteen years more women will hold Chairs in Classics, Ancient History, and Archaeology.

3.2 Casualization

Casualization is clearly a pressing concern. Half of respondents answered a question directed exclusively at non-permanent employees; 32% of those who answered have less than a year’s employment security. 35% of all respondents cannot support themselves on their income from Classics. This includes 35% of those who identified themselves as Early Career Academics, and 72% of research postgraduates.

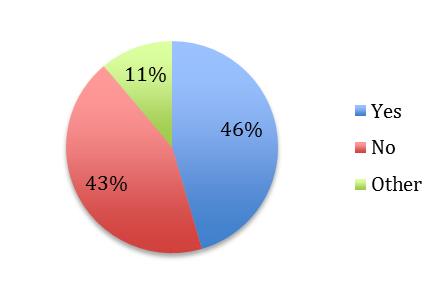

A question asking about the effects of casualization was directed specifically at Early Career Academics and postgraduates. There were 242 responses, of which 46% had experienced the effects of casualization on their employment. A free-text box asked for comments on how they had experienced those effects. The answers provided a depressingly repetitive picture. Respondents were concerned both for their current situation and for their career prospects. Stress and other threats to mental health were the most frequently mentioned issues. Casual employment makes it hard to plan ahead in terms of personal life, finances, including specific issues like being ineligible for a mortgage, and research. Some respondents faced difficulty accessing resources, including libraries and email, either because contracts do not continue over the summer or because frequent moves mean starting afresh every year. Constant moves around the country are draining, and many casual employees end up with very long commutes because they cannot move house for short-term contracts. Pay is low, and casual employees are often not paid for essential parts of their jobs, such as teaching preparation or marking which continues after the end of the official contract. Many are not paid at all for the summer. Multiple respondents noted that their actual hours worked took them below minimum wage. The outlook was pessimistic: several respondents mentioned that they saw jobs which in the past would have been permanent be given to temporary or casual employees.

For Early Career Academics and Postgraduates – have you experienced the effects of casualization in your employment?

It is instructive to compare the experience of our respondents with the data provided by the Council of University Classics Departments (CUCD). From 1986, the CUCD has gathered information on the total number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) in Classics departments all over the UK. From the academic year 2001/02, it began collecting more detailed information, indicating part-time vs. full-time employment and permanent vs. temporary positions (see here the most recent publication). This focus makes the data immediately relevant to the issue of casualization as it pertains to the field of Classics. The CUCD has not yet gathered information about the gender or ethnicities of people working in Classics in British Higher Education Institutions. To widen the scope of this annual data-gathering effort, including gender and ethnicity factors would be a beneficial integration. In this way, the CUCD statistics would help to monitor the gendered and ethnic fabric of Classics departments in the UK.

4. Gender in Professional Interactions (Katherine McDonald)

This section was made up of three questions, with respondents being invited to contribute examples with their answer if they chose. The free-text questions which invited respondents to give examples from their experiences ended up overlapping considerably. Responses included discussions of discrimination and negative attitudes towards women in the workplace, difficulties for women in recruitment and promotion, problems related to parenting in academia, sexual harassment, and bullying.

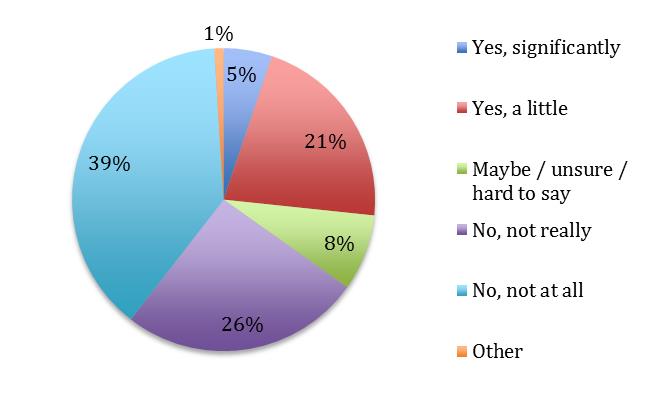

In a professional environment have you experienced discrimination on the basis of your sex, gender, sexual orientation, or issues associated with these?

For this question, 32% of respondents reported that they had experienced discrimination based on their sex, gender or sexual orientation. A further 44% thought that they had not experienced such discrimination, and 24% were not sure or replied ‘Other’.

Of these, over a quarter of respondents (118) added to their reply with a longer answer. Some of the most common complaints included: not being heard or not being taken seriously; being given tasks that were seen as undesirable or offered lower rewards (such as higher teaching loads, higher expectations of administrative and pastoral work, and even making the tea) and being prevented from taking up desirable or highly rewarded tasks; and women’s research not being taken seriously (particularly research connected with gender and feminism). Several respondents reported being warned off feminist research if they wished to remain employable. Being pigeon-holed into certain roles or modes of behaviour was another common theme of the answers, with respondents expressing frustration that they were expected only to do feminist or woman-centred research, that they were expected to be naturally ‘nurturing’ towards students, or that they were expected to act in a particular way in interpersonal interactions in their departments.

Problems with students was another common element in the survey responses, with clear concerns from respondents that students do not take female teachers and lecturers seriously or give them poor evaluations – with the introduction of the Teaching Excellence Framework this problem needs to be addressed. Conversely, several students also mentioned that their teachers and supervisors had had lower expectations of women as learners.

A number of respondents replied in this section that women with children, or women of childbearing age, were at particular risk of these kinds of problems. Several respondents highlighted that gender intersects with age, ethnicity, and sexuality – young women, women of colour, and gay women felt that they had a particularly difficult time being taken seriously.

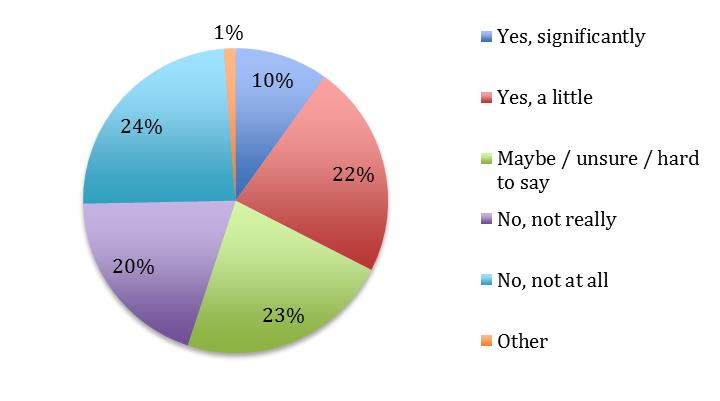

Have issues of gender, sex, or sexual orientation affected your career progression?

Of 399 responses, 22% felt that their career progression had been significantly or a little bit affected by their gender, sex or sexual orientation. 28% felt that it was hard to say.

In the comments, there was a particular focus on pregnancy, breast-feeding, and parenting as problems in career progression. Respondents felt that returning after a career break or maternity leave was particularly challenging. Many respondents also felt that men were more likely to get recruited to permanent positions and more likely to be promoted or encouraged to apply for promotion, though three respondents felt that recruitment was now favouring women.

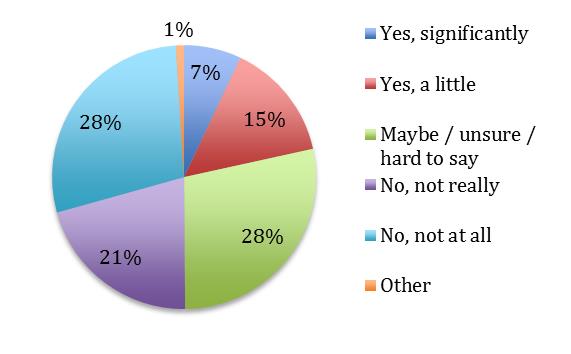

Have you experienced unwelcome and/or inappropriate sexual behaviour in a professional environment?

For this question, 25% of respondents said that they had experienced unwelcome or inappropriate sexual behaviour. 39% said they had not experienced any inappropriate sexual behaviour at all, but a number of these respondents nevertheless reported having witnessed this behaviour. A small but significant number of the comments included reports of very serious instances of sexual harassment, assault, intimidation, and bullying.

Many respondents brought up incidents of inappropriate sexual behaviour or comments from their students; other reported being the target of sexual harassment by their teachers, lecturers, or supervisors. In particular, female graduate students identified themselves as targets of sexual harassment and unwanted sexual attention by their supervisors, colleagues and academics in other contexts, particularly at conferences. The repercussions of this dynamic in academia should be taken very seriously.

There were also four suggestions in the comments that things are improving for women in academia in this regard – sexual harassment and bullying are taken more seriously by management and Human Resources, and overt misogyny is not seen as ‘normal’ – but there are nevertheless still serious problems being experienced across the age groups. A number of respondents commented that these problems seem disproportionately to affect groups which are already vulnerable, namely young women, women in minority groups, and women with children.

5. Gendered Work: Parenting and Caring (Victoria Leonard)

In this section the questions were designed to ascertain information about parenting and caring responsibilities not as a distinct personal activity but as an inextricable part of a professional career. The questions fell broadly into two categories, asking respondents about balancing parenting or caring responsibilities and a career, and the facilities provided by places of employment.

Have you found it difficult to resolve conflicts between your personal or family life and career?

The survey asked if respondents had found it difficult to resolve conflicts between personal or family life and their career, and at 63% overwhelmingly the response was yes. The question ‘Has the issue of career progression and the nature of academic life affected your parenting and caring choices?’ produced a more mixed response: 40% of people affirmed that this was the case, but many participants found that the question was irrelevant, not having such responsibilities.

When asked if taking on parental or caring responsibilities had harmed participants financially, 49% of people felt that it had. A majority of 35% of people were unsure when asked if they felt that their employer offered adequate institutional support for those taking on parenting and caring responsibilities. This reflects a lack of knowledge, suggesting that such issues are not prominent in HEIs and expected standards are variable. Over 33% of people felt that institutional support was inadequate.

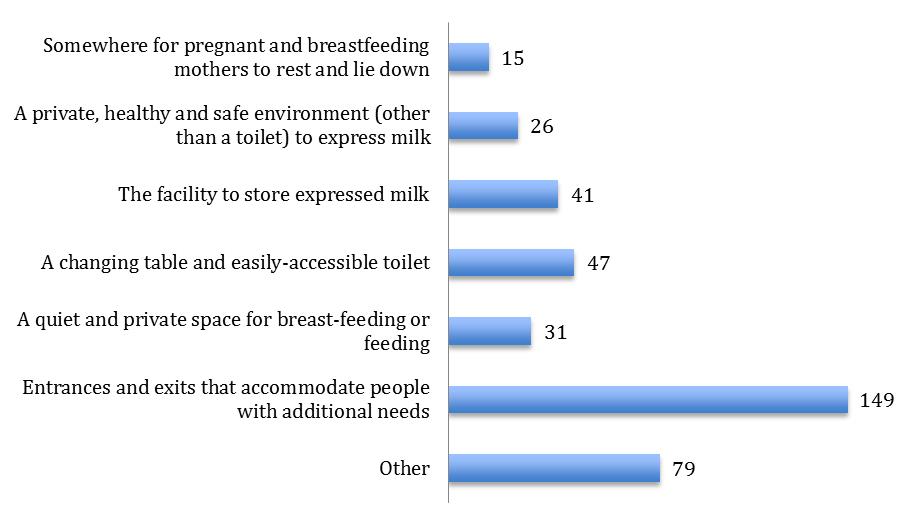

Does your place of employment provide child-friendly facilities?

When asked about child-friendly facilities provided by employers, 62% answered that their place of work had entrances and exits that accommodated people with additional needs. But only 6% of people said that there was somewhere for pregnant and breastfeeding mothers to rest and lie down, despite this being a legal requirement under the 1992 Workplace Regulation.[1] Less than 20% of people said that their place of work had a changing table and easily accessible toilet, a fundamental requirement for young children.

When asked about day-care options, 40% of people were unsure about the day-care options offered by their place of employment. This could suggest that many of the respondents do not have parenting or caring responsibilities, but it nevertheless demonstrates how hidden such issues are despite their fundamental importance for people balancing parenting or caring responsibilities and employment. When asked if their place of employment encourages the presence of children, only 21% could answer affirmatively.

In summary, responses to this section of the survey provide a depressing insight into parenting or caring whilst working. The impact on the careers and finances of people with parenting or caring responsibilities is significant, with inadequate support from employers to counterbalance this. Many of the issues around combining professional employment with the demands of the family are hidden, physically within institutions in the lack of provision, but also in terms of knowledge about what support is available, such as the provision of childcare and the acceptability of children at work.

[1] http://www.hse.gov.uk/mothers/law.htm. Last accessed 24.07.2016.

6. Mental health and disability issues (Emma Bridges)

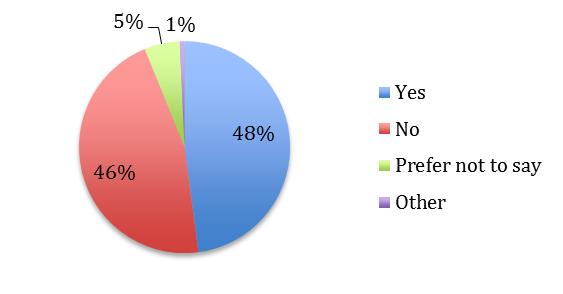

Of 407 respondents, almost half (195) answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Have you experienced mental health issues?’ Respondents were advised that there need not have been a formal diagnosis to answer ‘yes’.

Have you experienced mental health issues? (There need not be a formal diagnosis to answer ‘yes’)

The free-text comments in this section were revealing: some saw academia as a cause of their problems which included insomnia, depression, mental exhaustion, and anxiety, or as exacerbating pre-existing conditions, with the added stress brought on by, for example, the uncertainty of short-term contracts, performance-related pressures and deadlines, or workplace conflict and bullying. But some reported positive effects, citing the focus their work offers, and the support of colleagues and job satisfaction as being helpful. 32 respondents considered themselves to have additional needs or a disability and, as was the case with those who had been faced with mental health issues, the free-text answers revealed a range of positive and negative experiences relating to support given and discrimination experienced by individuals. Issues here ranged from problems relating to accessibility of facilities/buildings or specialist equipment, lack of training for managers and administrative staff on equality issues, and the failure of other academics to recognise an individual’s needs.

As several respondents pointed out, detaching issues faced by those with mental health problems or disabilities from issues relating to gender in the workplace is complicated, as (perceived or actual) discrimination in these cases might relate to more than one factor; this would therefore require further detailed work to unpick. Nonetheless, what the responses did reveal is that levels of support and understanding vary widely between institutions and departments. Perhaps the key point to note here should be that, at a local level, individuals can make a significant difference: by showing empathy; by challenging entrenched attitudes and behaviours; and by encouraging a culture of openness about mental health and disability issues.

7. State of the field (Irene Salvo)

The objective of the last section of our survey was to gain an overview about the perception of women in Classics, what challenges they face, and how the WCC can contribute to implementing real changes in the current environment.

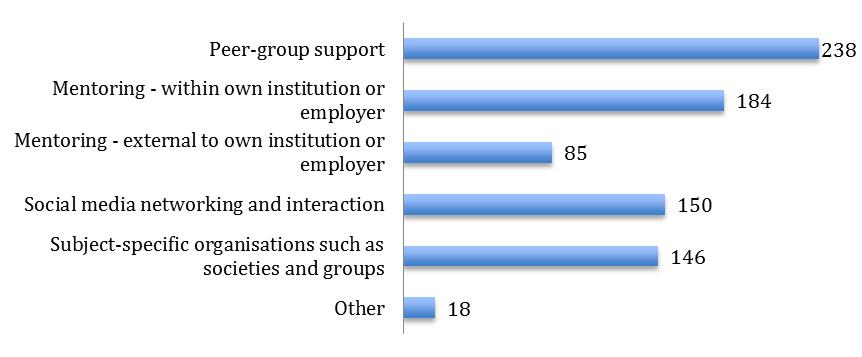

We asked what kind of support is currently available to classicists, and respondents had benefited especially from peer-groups, institutional mentoring programmes, social media interactions, and professional societies.

What kind of support do you currently find beneficial?

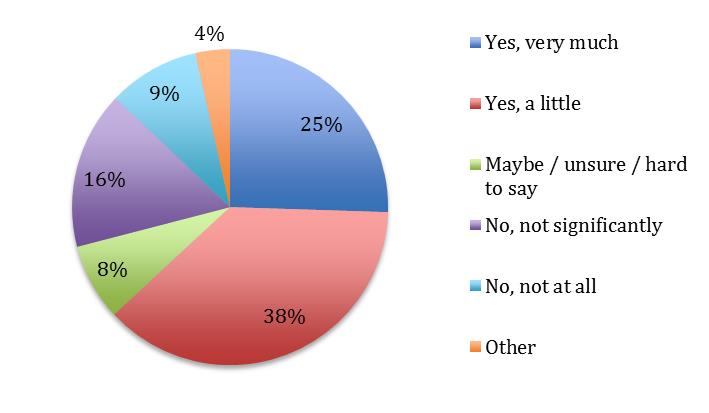

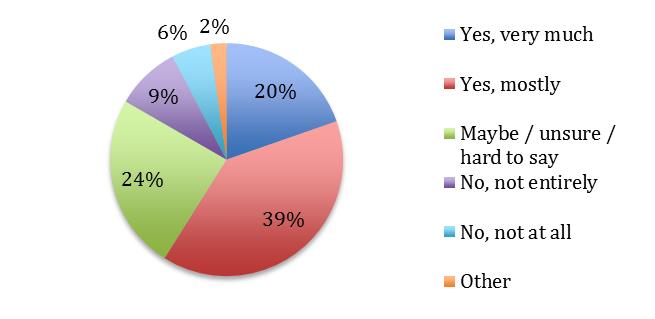

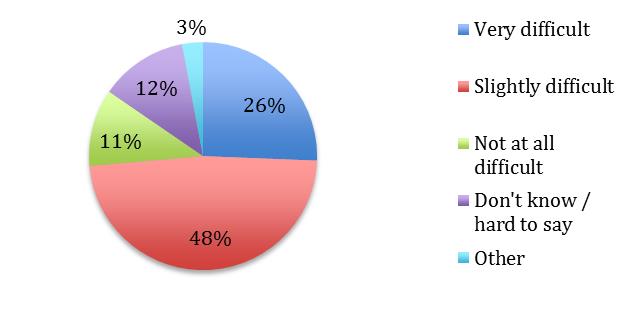

The two following questions focused on the perception of the degree of difficulty of career progression for women. 59% of respondents found career progression to be more difficult than for male colleagues. 74% perceived career progression to be ‘very’ or ‘slightly’ difficult for women.

Do you find the career progression of women to be more difficult than that of men?

How difficult do you perceive career progression to be for women in your field?

This last question allowed respondents to specify in a free-text box what the most difficult challenges were. Problems and issues already mentioned in previous sections recurred here. These included: career progression, promotion, and recognition; the rarity of leadership roles or international key research roles for women, with more pastoral care, teaching, and admin tasks assigned to female colleagues; lack of confidence; not being taken seriously, isolation or even discrimination for women doing gender-related research; scarcity of women in steering committee panels, review boards or interview panels; students’ feedback discriminatory to women; no mentoring programmes for women; expectations of long working hours, with a tangible stigma on those who request a better work-life balance. Parental and maternity issues, childcare, and caring responsibilities formed the other great problematic area, especially because children are still primarily the responsibility of women. Many respondents wrote that they are delaying starting a family, or have decided not to have children in favour of their career. Casualization often exacerbates family related problems, since temporary jobs rarely offer maternity leave or pregnancy allowances. Sexual harassment and everyday sexism was the third greatest area of challenge. Intersectionality with other issues was also prevalent; for example, a young black woman is more likely to face discrimination. Some respondents rightly underlined that in the current job market men and women alike are struggling with an arduous career path because there is a general lack of permanent positions, and gender may not be the main problem. This is true, but it is also undeniable that gender has (at the very least) the potential to hinder, complicate, and delay an already difficult path for female Classicists.

To our final question, ‘what aims or initiatives would you like to see advanced by the WCC in the support of women’, we received a great deal of precious positive suggestions, although some respondents exploited the anonymity of the survey to use this section to vent their spleen against gender-related research, and victimized men complained about the gender-based discrimination they suffer.

The majority of respondents asked for training programmes tailored to women and early career researchers, mentoring from established women in Classics, networking workshops and sandpits, a WCC panel at the Classical Association conference, and a dedicated feminist conference organised by the WCC. Respondents expected action in advocacy and lobbying, such as encouraging conferences to provide childcare facilities; the improvement of REF rules concerning caring and maternity; childcare in Higher Education Institutions; raising awareness of the importance of work-life balance; more transparency on gender and career progression statistics; and greater attention to all-male panels at conferences or committees. Other respondents requested more funding and scholarship opportunities (e.g. for conference travel or publication costs), and events with school teachers and pupils.

There was unequivocally a widespread need for emotional and moral support, for a friendly, open space where one can freely talk, speak out, and be heard. This space could be physical, thanks to meetings organised also outside of London or Oxbridge, or virtual, via social media and blogging. This section of the survey gave voice to a clear call for a greater equality in Classics in general: the image of our field needs to be transformed to be less elitist and more inclusive. Furthermore, gender is not just about women, and not just about white, straight, biologically born women.

CONCLUSIONS

With greater visibility for female academics, more women in permanent jobs, and proper parental leave, the situation facing women in academia has improved in some ways since the 1970s. But especially with pay inequality, the rise of short-term contracts and increasing casualization, the career path for female classicists is strewn with unknown obstacles, and the process of navigation is complex, challenging, and at times insurmountable. Certain barriers to progress are clearly gendered, as demonstrated by the data on sexual harassment. On one level, given that half of employed classicists are female (excepting senior positions), the results of the WCC’s survey are a testament to the resilience and resistance of those women. On the other hand, the survey shows that much still remains to be done, and that there is a plethora of measures the WCC can take to improve the situation.

Early Career Scholars are seeking more guidance and networking possibilities in order to be better prepared for an academic career. Considering the HESA data mentioned above, with a majority of female Classicists under 35, it looks like the voices of an ever-growing number of women entering the field are confronted with an authority and power that is predominantly male, with women often excluded from senior and leadership roles.

Our respondents have reported worrying experiences of student and staff victims of sexual harassment. Furthermore, our survey clearly suggests that childcare facilities are undeveloped, and this lack of support impedes the progress of working parents and the creation of a working environment in which staff can find a good work-life balance. Finally, a changing of individual and institutional attitudes to disability and mental health issues can contribute to a safer and psychologically healthier climate for everyone in academia.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie writes: ‘gender as it functions today is a grave injustice. I am angry. We should all be angry. Anger has a long history of bringing about positive change.’[1] Reading the 417 stories shared by our respondents, our reactions were anger, astonishment, frustration, and sadness, as well as hope and inspiration. Very often we found ourselves in those stories. The survey represents, then, a valuable opportunity for the WCC to act directly upon the insights the community of Classicists has offered, and we thank all those who generously gave their time and experiences in support of this endeavour.

[1] Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, We Should All Be Feminists, London 2014, 21.