Eating Ovid: An Experiment in Staging Shakespeare’s Classical Sources

After our successful and thought-provoking feminist pedagogy event in July, we invited the speakers to write up their spotlight talks as blog posts, to share their experiences with our wider readership. Our first post is from Stephe Harrop, Lecturer in Drama (Shakespeare and the Classics) at Liverpool Hope University.

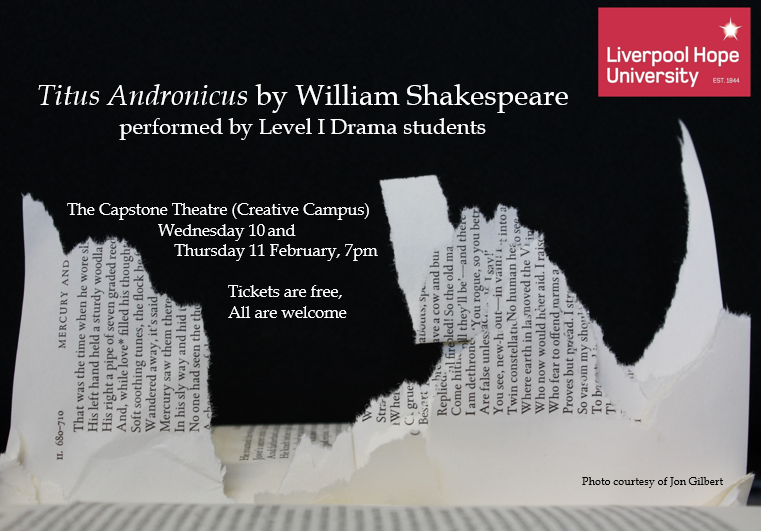

This post reflects on an undergraduate production of Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus I directed in spring 2016 at Liverpool Hope University. This would not have been my first choice of play for a high-stakes student assessment with a second-year cohort I was only just getting to know, so I want to start by thanking the group who would become the Titus Andronicus ensemble for suggesting such a challenging project, and for their stamina and creative courage throughout. I’m also grateful to my colleague Louise Wilson, early modern scholar and book historian, for her unfailing insight and support.

Titus Andronicus is both crammed with classical allusion, and (in)famous for its extreme, often sexual, violence, many of its worst excesses directly drawing inspiration from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, with the tale of Philomela-Tereus-Procne a recurring point of focus. In the play, Titus’ daughter is raped and mutilated in an attack explicitly modelled on Tereus’ treatment of Philomela (2.3.43-44), though calculated to exceed its cruelties (2.4.38-43). There follows a long, poetically elaborate, and self-consciously Ovidian description of her mutilated body, delivered by Lavina’s uncle (2.4.11-57). In The Rhetoric of the Body from Ovid to Shakespeare (2000), Lynn Enterline highlights the ‘supremely literary origin’ of the acts ‘written on Lavinia’s body’ (8). She argues that despite Lavinia’s unwillingness ‘to be interpreted yet again by the book written across her wounded body’ her narrative is ‘relentlessly pulled back to the story of Philomela’ (8). Lavinia’s body becomes the page upon which male readers of Ovid forcibly inscribe their own meanings.

I knew, from the outset, that I wanted to include some of Shakespeare’s classical intertexts within our performance, giving students the opportunity to engage with Titus Andronicus as operating within an extended heritage of literary violence. I thought of using Lavinia and Young Lucius as a focus for these intertextual moments, since we know that Lavinia is literate, and before the play begins she’s been reading to and with her nephew (4.1.13-15). She’s a sophisticated enough reader to make jokes drawn from her knowledge of Ovid’s Metamorphoses in the moments before she is attacked (2.3.70-71). I pictured her, modern paperback in hand, reading Ovid aloud with Young Lucius. And then another image started to form in my head. Lavinia, mutilated and mute, with pages torn from her own copy of Ovid forced into her mouth. A woman reader, to borrow a phrase from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (1.2.89-90), ‘put to silence’. That’s where I started from.

This directorial choice had unintended, but important, consequences. First of all, it meant that multiple copies of Ovid’s Metamorphoses were present in the rehearsal room from the beginning of our process. In consequence, as we began to develop our physical skills as an ensemble, we were also beginning to explore the book as material object; something to be thrown, caught, dropped, recovered, creased, smoothed, passed from hand to hand. Then we grew bolder. We began to incorporate these books into scenes where, officially, they had no place, contexts in which they might be snatched, slammed, weaponised, ripped, their pages shredded, scattered, or destroyed. Ultimately, these books became a central component of the production’s minimalist aesthetic, their use not confined to the single scene in which Shakespeare brings a copy onstage in order for Lavinia to identify the likeness between her own experience and the story of Philomela (4.1). Wherever Shakespeare’s play performs violence upon bodies, we began to perform the same violence upon books. Ripped from Alarbus’ and Bassianus’ guts, spilling from Lavinia’s mouth and hands, bundled into a shawl to represent Aaron’s newborn son, and unceremoniously tipped out again to serve as Titus’ Ovid-inspired cannibal banquet, chewed, spat out (maybe even occasionally eaten), torn pages from the Metamorphoses became the physical stuff from which we created our Rome.

Reflecting on this process, it seems to me that live performance’s physical presence potentially allows us to place a new emphasis upon the materiality of classical texts, changing the range of things we’re able to do with and to them. We’re all too familiar with the idea that books do things to bodies. Current debates about curriculum content, trauma, and trigger warnings are predicated upon the (often unspoken) understanding that ancient literary materials may, in Alex Wardrop’s phrase, create ‘hurt at this moment, in this room, right now’ (18). (See, for example, recent reflections on the subject from Liz Gloyn, Fiona McHardy and Susan Deacy.) However, drama’s physical interactions make it a pedagogical context within which we can also do things to books, unsettling conventional understandings of classical text as inviolable, while students’ bodies may have been violated and damaged in all kinds of ways. In directing Titus Andronicus, I found that bringing copies of the Metamorphoses into the rehearsal space allowed my unease about the tragedy’s pleasure in re-playing Ovidian violence to assume a tangible, material presence. And, as these books became central to the ensemble’s creative process, I also discovered that transforming our thinking about canonical texts – acknowledging and exploring the material presence of the book, as well as the ancient poem it contains – can potentially open a provocative space for students to develop their own critiques of, and resistances to, a classical play’s re-performed atrocities.

Stephe Harrop, harrops@hope.ac.uk